Each day is the outgrowth of the day before, as today is the sapling for tomorrow's tree. Each thought is an outgrowth of the thought that precedes it, as each life is another concentric ring in the tree of eternal life. In each incarnation, whatever you do, wherever you go, whatever you think, all you do is meet yourself! And every life experience is to help you refine this self, constantly evolving it to a more perfect expression of your soul. —Anonymous

"Chris Maser is an all-too-rare voice of sanity in the global eco-crisis."

David Suzuki, Host

"The Nature of Things"

"Chris Maser is an eloquent voice for the earth and its living systems. For two decades and longer he has been at the forefront of the effort to understand forests, soils, and wildlife and calibrate human actions with long-term ecological realities. His effort to translate science, spirituality, and human needs is remarkable."

David W. Orr, Ph.D., Professor

Environmental Studies and Politics,

Oberlin College,

Oberlin, Ohio

MY HISTORY IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION

My history in environmental education began 1942, when I was three years old about to turn four. I kept wandering off into the little patch of forest near our home, which kept my mother searching for me. The forest was across a rather narrow arm of the golf course south of Corvallis, in western Oregon, where I grew up. To remedy the situation, she put a harness on me, snap a line to it, and snap the other end to the wire clothes line in the back yard to keep me tethered and within sight, while at the same time allowing me some flexibility of movement.

I entered the first grade in 1944, where I met Billy Savage on the first day of school, and we become friends. Billy lived just below the golf course at the bottom of a long hill about a mile and a half from my house and just a stone's throw from Squaw Creek, a small, deep, quiet stream. Although Squaw Creek, with its deep waters, was no place for us to play at age six, the ditch, paralleling the far side of the paved road, which separated the front of Bill's house from the bottom of the golf course, was lovely and flowed most the year. The road was infrequently traveled in those days (1944 -1950), so Madge, Billy's widowed mother, gave us permission to play in it.

The day Billy first showed me the ditch, I didn't know what to make of it. I stood for a time looking at it, feeling uncertain. The water's surface caught sun sparkles, which it tossed playfully about as it flowed in and out of shadows. It rippled and bounced in shallows and gurgled under overhanging banks. Swinging around a bend, it entered a deep hole, where in silence it caused submerged grasses to sway. Enchanted by their green hypnotic dance, I knelt for a closer look, and something happened deep inside, a feeling I can't explain but which to this day holds me captive.

Drawn closer, ever closer to the laughing water, I began crawling slowly along the bank peering into its ever-changing depths. Time slid by, silent and unnoticed in its passing, as I looked at this bug and that flower, all of which were new to my senses. So engrossed was I in my discoveries, I barely noticed the soft marshy place, where my hands sank into slimy ooze and my knees got wet. Then it was too late!

Tall brown-headed sentinels with long, flat, dark-green leaves, like medieval broadswords, closed ranks about me, creating a subdued, murky light. I began to panic, as lofty dead seed stalks rattled in the breeze like tiny demonic voices whispering in my ears.

I tried to back out, but I couldn't. The swords were between my legs. All about was a green and brown wall, under and through which water seeped. Where was I? All I could see was green and brown and water. I was getting wetter and wetter.

Where'd the ditch go? I wanted out! Which way's out?

I felt confused and lost. I had no sense of direction. Fear clawed its way into panic, and inside my head a child's voice screamed: "Which way is out? I want out! I want out!"

What's that sound!? Crunch. Scuffle. Crunch. Silence. My heart pounded as the silence deepened.

"Chris, where are you?"

"Here," I answered weakly.

"Well, come out of the cattails."

Turning, I crawled toward the sound of Billy's voice. The green and brown wall opened suddenly, and there was Billy not ten feet away on the side of the road. Relief flooded through me as my stifling surroundings gave way to open, airy sunshine.

I looked at Billy and realized that I had never had a friend before, so I couldn't let him know I was afraid. If he thought I was afraid, he might not let me come back to his ditch, and I would lose my only friend. Therefore, because the ditch was important to Billy, I decided it would became important to me too.

Over time, the ditch became for me a marvelous and wondrous thing, and it had only one purpose, to be my playground. I loved the ditch and all its mysteries. It was my own, private place in the world and that was sufficient unto itself.

My ditch was a place of innocence and wonder; a place of mystery and of boyhood imaginings; a place to touch the Earth, the water, and the sky. It was a place where the green arms of cattails; sedges; and rushes; and the tall, swaying grasses enfolded me, hid me, and bade me stay while I learned the songs of the seasons.

It was a place where the water spoke quietly of the harmonious cycles of life, where grasshoppers and crickets trilled, and gray-tailed meadow mice scurried along their secret runways. It was a place where wandering breezes carried the perfumes of flowers and the melodies of birds, where gaily colored butterflies dotted magical afternoons. It was a place brimming with life, a place where the harmonious cycles of the sun, moon, and stars guided a constant becoming as life flowed through death into life and the seasons melted one into another. And it was the place where I learned about friendship.

But most of all, it was the place where I first began to understand that the smallest piece of anything was still a part of the whole and that to understand the whole, I must value the pieces. I not only began to see the eternal flow between the pieces and the whole but also I began the long, slow process of being born unto myself in the greater context of the Universe as one of Nature's pieces reflected in the spiritual and ecological perfection of that infinitesimal spot on Earth that my friend, Billy, and I called "our ditch."

It was here between the ages of six and twelve, that I was simply open to the mysteries of the Universe, and they were revealed to me in all their splendor. Here, within the banks of a humble, roadside ditch, I saw the crowning jewel of the Universe unfold. I saw life and death and change. I saw Creation, and I found God.

I say this because a ditch starts out as a raw, naked wound, a furrow in the skin of the Earth, for whatever reason it has been dug. Then Nature takes over, molding and sculpting the furrow with erosion, using wind and water, and ice as Her implements. Slowly the gapping furrow begins to round and crinkle as flowing water moves jousting grain and shifting pebble here and there. Little by little the ditch bottom loses all sign of human tool, and the once-raw wound becomes a labyrinth of nooks and crannies, each with a pair of eyes silently watching the world.

As the ditch's bottom transforms, Nature plants seeds along its banks, creating a backdrop of swaying grasses and brightly colored flowers, of protecting shrubs and stately trees. On this stage unfolds Nature's play, enacted with the animals that live along the ditch, burrow in its banks, and visit with the seasons, wherein each adds a touch of creativity to the overall effect. Crickets lead the orchestra, with birds as minstrels and butterflies as the chorus line. Add two little boys, and magically you have a portrait of the ditch that was to be such an integral, formative part of my childhood.

WHEN GRIEF TOUCHED MY SOUL

As a youth in the 1950s, and even as a young man in the earliest years of the 1960s, I could stand on the shoulder of a mountain in the High Cascades of Oregon or Washington and gaze upon a land clothed in ancient forest as far as I could see in any direction into the blue haze of the distance.

The land was clothed in unbroken, ancient forest as far as I could see in any direction.

My sojourns along the trails of deer and elk were accompanied by the wind as it sang in the trees and by the joy of water bouncing along its rocky channels. At others times, the water gave voice to its deafening roar as it suddenly poured itself into space from dizzying heights, only to once again gather itself at the bottom of the precipice and continue its appointed journey to the sea—the mother of all waters.

Throughout those many springs and summers, the songs of wind and water were punctuated with the melodies of forest birds. Wilson warblers sang in the tops of ancient firs, while the plaintive trill of the varied thrush drifted down the mountainside, and the liquid notes of winter wrens came ever-so-gently from among the fallen monarchs as they lay decomposing through the centuries on the forest floor. From somewhere high above the canopy of trees came the scream of a golden eagle, and from deep within the forest there emanated the rapid, staccato drumming of a pileated woodpecker.

These were the sounds of my youth. This was the music that complemented the forest's abiding silence—a silence that archived the history of centuries and millennia as the forest grew and changed, like an unfinished mural painted with the novelty of infinite Creation.

The ancient forest of my youth.

By1960, however, I began to notice a change in the forest, one that filled my heart with dread. The warm summer winds, coming up from the valleys carry with them the faintest of roars. Chain saws were coming. That meant only one thing—devastation to the ancient forests I grew up loving.

Then something happened that forever changed my life. It was the 13th of October 1961, and I had just turned 23. The sky was a pure, cloudless blue. The snow atop Mount St. Helens glistened in the sun across Spirit Lake, which is in the Gifford Pinchot Nation Forest of Washington. I stopped eating the sun-ripened, sun-warmed black huckleberries and stood for a long time, a seeming eternity, on Grizzly Pass overlooking Spirit Lake. I had been in the mountains for three agonizing weeks, and in my heart I knew that I could never go back to the mountains of my youth. I would never again know the mountains as I had known them.

Sunrise over Spirit Lake and Mount St. Helens.

I had just spent three weeks struggling within myself, trying to figure out what I would do. I had seen virtually all of the places that I loved fall to the chain saw. The last one I had just left—the valley of the Green River.

I still remember the trail along the river as it flowed through the ancient forest that was unbroken for 50 miles in any direction when I first knew it. The trail was dappled with soft green and bright yellow light filtered through a canopy of vine maples amid the towering trees. It was cool and deep, and the western redcedar trees that lay on the ground across the old trail were so big that I could not climb over them. I either had to find a way under them or go around them.

Deep in the forest, far from any human habitation, there was a soda spring, where the band-tailed pigeons liked to drink and from around whose edge they ate the ripe blue-elderberries. As for me, I packed in some lemons and a little sugar and made the best lemon aid from the bubbly water. I also made syrup from the elderberries, flavored it with wild ginger and salal berries, and poured it over my hot cakes and pan-bread. In addition, the river in those days had so many native cutthroat trout that I caught them by dangling a dry fly an inch above the surface of the water. Deer, elk, black bear, marten, mink, blue grouse, and an occasional ruffed grouse shared the river with me as I fished for my supper.

I had last camped there in the autumn of 1959, with no hint of the clear-cut logging that had for years been working its way up the river. But this time (1961), as I rounded the last bend in the trail just before the soda spring, I was struck dumb and sick at heart by the view. As far as I could see there was one giant clear-cut with human garbage scattered along the miles of logging roads. I caught one fish—and it had a hook in its mouth.

That was the day I learned the depth to which grief could plunge my soul. From that day to this, I know the endless grief of seeing one more clear-cut, one more mountainside denuded, one more roadless area dissected and fragmented, one more landscape becoming a homogenous patchwork of monocultural plantations of trees.

One more clear-cut; one more denuded mountain side.

On that day in 1961, standing on Grizzly Pass looking down on Spirit Lake, I knew I faced the crossroads of my life. I knew I had to make a choice: flee into the wilderness of Alaska or Canada or face the cities I despised and fight for the survival of the forests I loved so much. I don't know how long I stood there, but the sun was setting over Mount St. Helens, and I still had miles to go. Like the Native youths who had gone before me into the sacred heart of the ancient forest, I left behind my youth. Unlike those youths of old, however, I also left my heart in the care of the land, for where I had to travel there were no sacred forests left.

Sunset over Spirit Lake and Mount St. Helens.

GRADUATE STUDIES

What the arrival of the chain saw meant to the forests I loved really came home to me in 1963 as I worked on my Master's Thesis, for which I studied red tree mice, whose populations were constantly decimated by clear-cut logging. The destruction of their habitat was particularly painful because I had grown to love the little, red mice so very much. In fact, each time my research necessitated killing one of them, I'd lock myself in my office and cry almost uncontrollably during and after the whole process. Once again the unrelenting grief of continual loss knocked at the door to my heart.

Keenly aware of my grief, I went to the only person with whom I could discuss it—Dr. Kenneth L. Gordon.

Ken, the professor in charge of my graduate studies, was an exceedingly gentle man of tremendous artistic talent in writing, drawing, wood carving, and photography, in addition to which he exhibited boundless creativity in his pursuit of natural history. Moreover, he, too, suffered from the same grief I did. But it was his philosophy of minimal, ethical disturbance of Nature, his gentleness with all things living, and his deep regard for the living spirit he saw in all things that still influences me, an influence that began with my barging into his office one day in a blind rage over the destruction of a forest wherein I was studying red tree mice.

A red tree mouse in my hands.

Telling me to close his office door, he motioned me to sit while he tapped the spent tobacco from his ever-present pipe, refilled and lighted it. He then regarded me for a long, silent moment, as though making up his mind about something.

"Chris," he said, "you'll find in life that most people are so busy with their day-to-day affairs they scarcely notice anything else. I came here to Oregon in 1926. It was much more peaceful then with far fewer people. In fact, I think I drove every road in the state within a decade. I've seen a lot of destruction of the state within these past thirty-seven years [it was now early 1963]. That's why I started photographing what I call 'The Passing Scene.' It's my way of remembering the part of my life that's fading into history, never to return. Creating an archive of visual memories is my way of softening my grief."

"Doc," I interrupt his slow, methodical speech because—as impolite as it was—experience had taught me that Ken was easily sidetracked into examining hitherto unexplored, mental rabbit trails, "what are you getting at?"

"Well," he continued, "like me, you'll see much that you love disappear in your lifetime before this modern notion of 'progress.' And, like me in my youth, you'll feel powerless to stop it. In fact, I came west when I graduated from Cornell with my Ph.D. because I loved the open country. I wanted to get away from the destruction I saw on the East Coast. But I couldn't get away from it. It's here too!"

"How did you even know about the openness of the West if you were at Cornell?"

"Because I was raised in Fort Collins, Colorado. Anyway, I've found that anger and force net only despair. You've got to examine your feelings, and then go through them to reach the rational logic that will tell you what to do."

"How," I ask impatiently, "do I know when I've reached this 'rational logic' of which you speak?"

Ken went to the small blackboard on his office wall, picked up a piece of chalk, and drew the simple depiction of stairs. Pointing to the top step, he drew a horizontal line outward from it and said: "This was Oregon as I saw it in the late twenties and early thirties, and to me that was the optimum."

"Okay," I ventured, "but I was born in 1938 and gained my perception of Oregon at its optimum in my teens and early twenties as I wandered the trails of the Coast and Cascade Mountains, as well as the high-desert steppe east of the Cascades. But now I find most of the places I love already falling to the roar of chain saws."

Ken regarded me for an instant. Then went down two steps to 1950 and drew another horizontal line: "This is when your perception of Oregon began to emerge." Drawing a third horizontal line outward from another step down (1960), he continued, "This is when you really began to notice the changes taking place. It is part of the human condition to notice change at intervals. If you love Nature and the natural world around you, then you have the sensation of descending the stairs from top to bottom, with each step a loss of something cherished. But, if your interest in life is tied to something like technology, then you ascend the stairs with each new invention, such as the chain saw. In the end, the desirability of a given change is based on one's perception of the circumstance that precipitated the change."

"Ken, this is clear," I said with some frustration in my voice, "but how will I know when I've reached this 'rational logic' you speak of?"

"You'll feel it; it's an intuitive sense of harmony with what's right, with what will work. For instance, did you ever consider that most people don't even know the consequences they cause in and to Nature simply because they're uninformed. They're not bad people; they're just ignorant. Not stupid—ignorant! Remember, scientists tend to write for and speak to one another; they've scant interest in informing the public. Perhaps that is something you could do—educate the public."

"How?"

"When the time's right, you'll know what to do and how to do it. But first, you have to learn the basics. You have to pay your dues before you can speak. So, back to your studies!"

Ken always saw something to which others were blind. He saw the spiritual laws that lay behind all science and technology, the spiritual laws that underpinned the Universe. And in his quiet way, he planted in my mind, heart, and soul the seeds of his vision that I might one day see what he saw, a truly spiritual world.

Ken and me on December 14, 1965. I had just passed my final exam for my Masters of Science Degree.

Following that 1963 visit with Ken and my graduation from college, I came across a couple of quotations that recalled Ken's counsel from the shadowlands of my memory: "When the time's right, you'll know what to do and how to do it." The first comment was penned by Thomas Jefferson in a letter to William Charles Jarvis on September 28, 1820: "I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves, and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education."

"Enlighten the people generally," wrote Jefferson, "and tyranny and oppression of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day."

The second remark came from British economist E.F. Schumacher who, while sharing Jefferson's notion about education, also saw its folly in contemporary industrial societies: "If Western civilization is in a state of permanent crisis, it is not far-fetched to suggest that there may be something wrong with its education. More education can help us only if it produces more wisdom."

BEYOND GRADUATE SCHOOL

From the day I watched the sun set over Mount St. Helens in 1961 to this, I have spent my life working to help society understand and accept the ecological and social value of diverse ecosystems in all their stages of development—ecosystems that are inseparable from and vital to the well-being of humanity through all generations.

Because knowledge equates to the power of choice, and access to knowledge equates to empowerment, I have consciously heeded Ken's counsel for just shy of four decades. In keeping with that counsel, I continually study. As well, I write, speak, and teach about our human relationship to the environment and our adult responsibilities to the children in order to "enlighten" the "people" about the inviolate principles that govern Nature's ability to produce the natural wealth that sustains us humans as individuals, communities, and societies—present and future.

Trained in zoology and ecology, I worked for 25 years as a research scientist in agricultural, coastal, desert, forest, valley grassland, shrub steppe, and subarctic settings in various parts of the world before realizing that science is not designed to answer the vast majority of questions society is asking of it. Science deals with an understanding of bio-physical relationships, whereas society asks questions about human values. Question about human values must be answered socially because they are beyond the realm of science to address.

I gave up active scientific research almost two decades years ago and have spent the intervening time working to translate science for society and society for science in an effort to unify scientific knowledge with social values in designing sustainable communities in a reciprocal relationship with their landscapes, part of which entails resolving conflicts. To this end, I have facilitated the resolution of conflicts over a variety of issues related to: forests and forestry, water, grazing of livestock, fisheries, community development, urban planning, and community open space.

I am now an author, international lecturer, and facilitator in resolving environmental disputes. I also help communities create vision statements and assisting local people in designing sustainable communities and sustainable forestry practices. As such, I am committed to telling it as I see it in order to give people an honest appraisal of their social-environmental problems based on extensive experience. Because I have been privileged to have such a broad background, I can help people to find innovative ways of planning a sustainable future for themselves and their children, of resolving their conflicts, and uniting their community in a healthy relationship with their surrounding landscape from whence comes the community's natural wealth. This is important, because people can most easily deal with required changes when they feel safe and know someone is there who cares about them enough to guide the process as gently as possible, all the while protecting their dignity and looking out for their well-being. As one means of accomplishing this, I teach local people how to ask and research relevent questions so they can learn from their own experiences and thus become self-empowered and increasingly independent from the need for costly, outside consultation.

In the end, everything I do is based around environmental education. It is the only way I know how to live and fulfill the counsel Ken Gordon, my friend and mentor, gave me so very many, precious years ago.

Chris,

I was sitting under an old New Mexico juniper with my 4 year old yesterday, with some fossil seashells and palm wood he'd found amongst the cow pies.

We were talking about a kangaroo rat's seed caches he'd found, and he asked what happened to rodent poop and why it wasn't everywhere in the desert.

Talking rodent poop with Joey made me think of Chris Maser and the thanks I've been meaning to send your way for a few years now.

I grew up in the Oregon cascades, skipping school to hike the Salmon/Huckleberry Wilderness. I had jars of slime mold and alcohol-preserved shrews and mice and a mountain boomer in our barn.

In high school, I read Forest Primeval, and a fair number of your and Jerry Franklin's technical papers. Those were my introduction to the scientific literature.

I wound up getting a degree in evolution and ecology, did survey work and ecology in Sonora, British Columbia, Australia and Guyana . . . which has got to be a global epicenter for bat biodiversity . . .

I'm a writer and am belatedly wrapping up a graduate degree in nuclear and bioweapons proliferation issues and US foreign policy.

Your and Jerry Franklin's writings in the late 80s and very early 90s put me on that path, and I've meant a few times over the years to send my thanks.

I look forward to reading your books again, this time with my boys.

So: thank you.

I hope you're well, and look forward to getting reacquainted with your

writing.

Best wishes,

Bryant Furlow (2008)

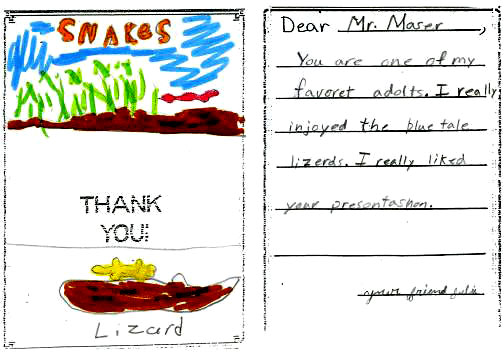

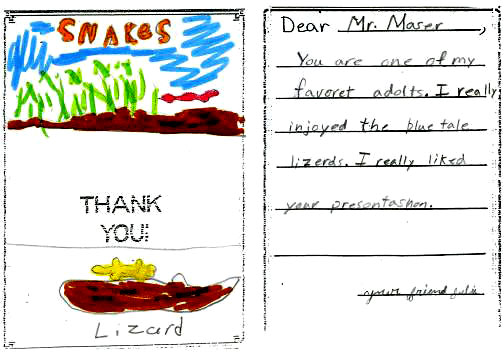

Julie was in the fourth grade when I visited her class.

IF YOU THINK I CAN HELP YOUR GROUP, SCHOOL, AGENCY, OR COMMUNITY, PLEASE CONTACT ME

TOP | HOME | SITE MAP | RÉSUMÉ | SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY | VISION AND LEADERSHIP

CONFLICT RESOLUTION | ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION | FORESTRY | PUBLIC SPEAKING | BOOKS

STORIES | MUSINGS | ESSAYS | CONVERSATIONS WITH FEAR | LIFE SERVING LIFE | BIBLIOGRAPHY

SELECTED SPEECHES | LINKS | SEARCH SITE

Chris Maser

www.chrismaser.com

Corvallis, OR 97330

Copyright © 2004-2011. All Rights Reserved.