IN EMPTINESS IS SPIRITUAL FULFILLMENT

by

Chris Maser—with Zane Maser

Emptiness is letting the chatter of the mind die away and productive hands be idle. In emptiness one accesses the law of Wu Wei, which literally means "without doing, causing, or making." It is understanding that in the emptiness of inner solitude, where one melds in consciousness with the heartbeat of the Universe, there is nothing to do, hence nothing left undone. In this place of "effortless effort," of utter stillness, and inner silence one hears the great universal sound, the Voice of the Divine. It is here that all sages and saints have stood and received the Grail Cup.

When I walk through the gate of the high cedar fence surrounding my garden, I enter into a secluded place, a sanctuary of the soul, wherein worldly knowledge, incessant noise, frantic motion, aggrandized stimulation, and competitive ambition fall away. "If a man can be absolutely quiet" a Chinese teacher once told his students, "then the Heavenly Heart will manifest itself." Here, in the solitude of my garden, is the heartbeat of the Universe palpable.

It beats in the rustling of dragonfly wings about my pond and in the cold North Wind blowing far from its Arctic home; it is felt in the rain coming off tropical currents of the Pacific Ocean and is seen in the twinkling light from distant stars. It is in the howling fury of a Winter storm and the silence of a Summer's day when the world hangs limply in relentless heat. In this "wise silence," as Emerson termed it, is the eternal center, "the still point of the turning world," which is best expressed in the Sanskrit word purnata—a stillness that is completely full.

The antithesis of my garden's hush is the disenchanted outer world, where it is absolutely imperative to get somewhere and produce something. Yet, as Thomas Moore explains in The Re-enchantment of Everyday Living, time spent in a garden gets us nowhere. "A garden," he says, "entices us to slow down and stop," which, he adds, is an important dynamic of the soul, for anything of the soul requires time and a lowering of productivity and effort.

Gardening is thus a monk's way of nurturing the soul, which Moore calls a "fruitful silence," where movements of the soul are amplified. A life that honors solitude is a requisite for self-mastery, living with a sense of direction, and discovering the true song of one's own soul.

When thus I enter into my garden I am on holy ground at the center of the Universe, for all relationships begin and end therein as they are gathered up and given forth from the spirit of my being, which is diffused throughout the cosmos. In Muslim countries, the old part of their cities was called medina or "holy place." And so it is when you enter into your garden or medina, the center of the Universe is everywhere and nowhere.

One of the great classics of the East states that "the universe turns upon the axis of silence." It moves when we move and rests when we rest. If therefore, I am simply content to be in the moment, I am filled with the vast emptiness of inner solitude, which I long ago experienced in the deserts of Egypt when I was too young to understand.

There is a silence in the deserts of Egypt that wraps like a cloak around the heat by day and the cold by night when the wind is still and not a grain of sand stirs. On such a day in the Nubian Desert east of the Nile, one piece of ironstone dropped upon another can be heard by a Dorcas gazelle a mile away.

It is there, in the silent splendor of the desert, that the early Christian monks went to live that they might find emptiness. This is the contemplative life to which monks are called. The word "contemplative" means to cut out a space for divination, to set apart space for sacred use, for the building of an inner temple, as noted by Thomas Moore in Meditations. "Contemplation," explains Moore, is the primary work of the monk if he or she is to achieve the necessary emptiness in all things.

The early Christian monks, according to Moore, were experts at doing nothing and tending the culture of that emptiness. Their existence denoted a complete absence of drivenness. In the exact measure to which they were empty so were they in like measure full, for emptiness, instructs Brother David Steindl-Rast, is the necessary condition for fullness in all its forms.

One evening in that long ago, I sat down to rest on a large boulder of ironstone. As I surveyed the enfolding magnificence of the Nubian Desert, watching the waves of heat dancing in the distance, I had a profound sense of company. Looking around, I discovered that I was sitting on the same rock on which a Paleolithic man sat more than 15,000 years ago as he chipped hand axes from the ironstone. One of them lay at my feet.

Picking it up, I discovered the tip was broken. I could almost feel his frustration at breaking the tip just when he thought he had a finished ax. I felt a kinship with this artisan of antiquity and intuitively knew that time was only an intellectual construct that trapped my worldly mind, that behind the veil of illusion in complete stillness was the omnipresent unitive state. Because I so keenly felt the ancient one's presence, I also felt the roots of all humanity embodied in and passing through the craftsmanship of one man stored in the seemingly timeless silence of the desert.

As I sat where my Paleolithic brother had sat and pondered his countenance and frame of mind, I knew that I somehow stood on the shoulders of what he had learned and passed on when, to me, time seemed younger and the world seemed newer and more innocent. In that moment, I entered the emptiness of eternal solitude as one liberated in timelessness. All that existed for me was the presence and the touch of my Paleolithic brother.

I had thus entered an alternative place of being, which the mystics have called a retreat or vacatio—an emptying of ordinary life, which affords the opportunity for a different kind of experiencing. In the emptiness of this "lucid stillness," the mystic is able to live on a deeper level in order to be keenly attentive to messages that come from God, as Thomas Merton puts it.

Before you can experience the "lucid stillness," however, you must empty yourself, as a university professor discovered when inquiring about Zen from Nan-in, a Japanese Zen master. Nan-in served tea. He poured the professor's cup full and kept on pouring.

Nan-in replied, "like this cup, you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?"

Some years ago, I read about the Buddhist concept of the "Nothing" from which everything comes and into which everything returns, but I did not understand it. That night I had a vivid dream in which I actually entered the Nothing and found everything, a reality that I am not sure I can explain, but I will try.

In my dream, I passed gently through some kind of border or boundary and found myself without form in a formless gray, the color being more of a sense than an actuality. Blending into the formlessness as pure energy, I had ceased to exist in the morphological shape of a human being. I felt totally at peace, a kind of peace that permeated everything that merged seamlessly into and through me, leaving room for nothing but itself and so became everything.

I awoke the next morning with an incredible sense of peace and without fear of losing my identity beyond the veil because, when one has absolute peace, there is nothing else of value and so one has everything. To this day, when I still my intellect, I can enter the Nothing and, for the eternity of an instant, find everything in the amorphous, seamless feeling of peace.

Trying to explain the Nothing calls forth the memory of an Emperor in a far away land who, wanting to adorn his palace with a new and original painting, held a contest in which the greatest painters of the day were commissioned to paint a flock of geese just taking wing. Although many great painters presented the Emperor with works of delicate beauty, he chose for his palace the painting by a Taoist whose canvas was blank except for the upper right-hand corner, which held the foot of the last goose to take flight.

In the thinking of German poet Johann W. von Goethe, emptiness has an invisible power from which patterns emerge, much as a vase on a potter's wheel forms itself around the active presence of a hollow, without which the vase could not exist. The vase is simply the external shell of a specifically shaped void, which holds emptiness within itself. From India, the Heart Sutra adds:

I am myself such a vase, and life is the wheel upon which the Master Potter is molding and emptying me. And it is my singular goal in life to serve the still small voice within; thus, I must learn to empty myself of myself. And if I can find within a single-minded purpose, then I might also find complete emptiness or self-forgetfulness, and achieve both fullness and fulfillment, in keeping with the Sanskrit word apuruamanam, which means "ever-full."

Although I began as a solid lump of clay, I am discovering little by little what in life is valuable and what is not, and I am discarding the latter with no desire to fill the space left empty by the sorting out and relinquishment. "Give up what you do not want," suggests A Course in Miracles, "and keep what you do." Each time I discard the valueless, I find that spiritual peace not only abides within but also fills the emptiness to the exclusion of all else.

As I mature in spirit, and the sorting continues, I find, as Thomas Merton wrote, that to be truly silent, one must let go the yearning for recognition and cease worrying about making the right impression. Spanish mystic St. John of the Cross adds, in verse that has a Zen-like flavor:

Finally, when one is filled with and enveloped by total peace and the wanting of anything worldly becomes a foreign country, one abides in Divine emptiness, with its stillness and silence, in which there is nothing—and everything of lasting value is contained. Now when I go into my garden and simply sit with it, there are moments when the material world fades and I enter once again into the Nothingness of my dream, into the fulfillment of Divine emptiness, within which absolute peace overcomes the self and becomes the Self.

Exercise In Conscious Awareness

White Eagle, the spiritual teacher, once said: "If you read the account of John the Baptist in the Gospels, you will notice that the place in which he dwelt is described as a wilderness—the wilderness of the world, the chaotic condition of man's collective soul. We are all in a wilderness within until we begin to discipline ourselves and turn our soul-wilderness into a beautiful garden. The term 'wilderness' in fact stands for the state of chaos, loneliness, and unhappiness which is the lot of the soul before it is awakened [or emptied of the little outer self]." The conquest of oneself and the overcoming of egotism was the central aim of all the mystery schools of the past.

Through the ages, self-emptying has been a central theme of mystics and has been called by many names: self-naughting, self-extinguishing, being unselfed, self-forgetfulness, self-achieved submission, being self-slain, and self-abnegation. For instance, Sri Krishna, in talking to Radnu about his flute said, "look, it's completely empty so I can fill it with my divine melody." Radnu represents the human soul longing for union with the Divine.

The process towards self-transcendence is meant to transcend

the mortal life of fears, worries, opinions, and wants for spiritual realization. Death of the ego is the purpose of all disciplines of the spiritual life, which is a letting go of the overshadowing worldliness. It has been called the "second death" in the Biblical Revelations, where one must die-to-self or die away from the self. Meister Eckhart terms this second death "a mighty upheaval."

People of today, when confronted with the concept of renunciation of self-will and dying to their separateness and selfishness, immediately believe they will lose their personal identity and freedom of choice. They believe they risk losing their independence and autonomy, but what they actually lose is the sense of self as a small, limited personality of the physical life, as the above mystics clearly attested. Carl Jung plainly describes this moment of realignment as the relocation of the center of gravity of the personality, from the ego as one's center to a center greater than one's self.

With this as a context for the value of relinquishing some of the outer self, begin now as you are sitting comfortably in your quiet place to shift your awareness from the clutter and clatter of the outer world to the peace and quiet of your inner garden. You may notice, when first arriving in your garden, that you are making too much noise with the busy activity of your mind to see, hear, or experience its peace and quiet. As your shoulders relax, feel all the cares and tensions melting away. Let go now any mental and physical tightness or strain in your body; be still and comfortable. A soothing relaxation is spreading through your entire body.

Notice that your breathing has become more quiet and peaceful. Feel its comfortable, serene rhythm as you begin to experience the feminine Nature of life, where the less you make of yourself, the more you are. The wisdom of the feminine is in opening and letting go in order to become. The greatness of the feminine comes from knowing within the center of your being how to empty yourself of your ego's will and become receptive to unconditional service.

Feeling so pleasantly relaxed, you find you are being gently led through the now familiar gateway of your inner garden. You have once again entered the special place of your own creative imagination. Open your senses to the full array of sights and sounds. With each breath, feel the transforming power of Nature's original innocence.

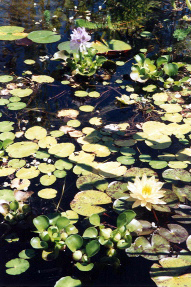

You feel most drawn to the center of your garden to the still pool of azure water. Remember the absolute peace and refreshment here as you sit comfortably beside the pool. A soft breeze caresses the trees and the birds sing about the harmony of all life. You feel the all-satisfying fullness and richness of divine life here beside the pool.

Again you notice that on the still water floats a pure white water lily. White is the perfect blending of all colors of the rainbow, and the lily is the symbol of surrender and relinquishment. You realize, as you gaze at the lily gently unfolding in the sunlight, that each part of life in this garden exists in a perfect state of resonance with every other part. The longer you gaze at the lily, the more you become the lily through the joyful emptying of self-forgetfulness. Now your little self is simply open to the will of your higher Self, the Will of the Divine. When you are empty of yourself, you are completely full of that upon which you dwell.

Now, thoroughly empty of the self-will of the ego, your soul merges gently, softly into the union of cosmic life. Empty of the ego, you have traveled a long way on the path of spiritual fulfillment and liberation, the path of self-transcendence to Self-realization.

Remain here for as long as you wish, breathing in the purity and the fragrance of the white lily as you bask in the gentle golden sunlight. You feel as empty and yet as full and satisfied as you have ever felt. When you are ready and want to return to outer life, walk slowly, softly back through your spacious garden of lawn and vibrant flowers. Retrace your steps through the gateway.

Slowly and gently breathe your way back to the consciousness of your room, your body, and the greater world about you. Be aware of the sense of harmony and wellbeing you may feel.

If you want to know how empty you are of your ego's will and how filled you are with the Will of God, go one day without using the personal pronoun I. Keep track on a piece of paper of every time you use I. At the end of the day, you might think of this simple prayer for your soul's journey: Thy will, not my will, be done that I may serve selflessly in life wherever I can do the most good.

Spring

Summer

Autumn

Winter

©

© Chris Maser and Zane Maser 2005.

This piece is excerpted from the American edition of: "The World is in My Garden: A Journey of Consciousness," White Cloud Press, Ashland, OR 287 pp. (2005). For more information, see the "Book" page of this website.

The European edition was published in 2003 by Polair Publishing, London, UK. The European edition has a different subtitle: "Using Gardening Issues to Illuminate Universal Concerns."

His visitor watched the overflow until he could no longer restrain himself: "It is overfull. No more can go in without overflowing."

Form is no other than emptiness,

Emptiness is no other than form;

Form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form,

… All phenomena are emptiness/form.

In order to arrive at having pleasure in everything,

Desire to have pleasure in nothing.

In order to arrive at possessing everything,

Desire to possess nothing. ,

In order to arrive at being everything,

Desire to be nothing….

![]()