Harry and Me

by

Chris Maser

I had met Harry Hoogstraal in Cairo, Egypt, 1963, and we became friends. Harry, a world renowned authority on ticks and tick-borne diseases, had given me, a scientific novice, some very sound "fatherly" counsel about scientific studies and publications that was to guide my career for more than a quarter century.

Harry's house in Maadi, a suburb of Cairo. I took these photos in September 1966 on my way to Nepal.

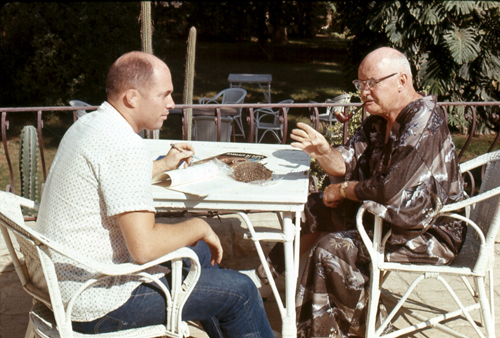

Cornelius B. Philip and me at Harry's house. Cornelius, a medical entomologist, was Director of the Rocky Mountain Laboratory. Saaid, Harry's house keeper, took this photograph in 1966.Harry, an enigma in many ways, was an exceedingly generous person and simultaneously a master of control. One of the loneliest people I've ever met, he was loved by his innumerable friends.

Harry liked the work I had done in Egypt, and when he asked if I would work in Nepal collecting ticks for taxonomic and epidemiological studies, I agreed. And yet, two of the most important lessons I learned from Harry have little to do directly with science.

The first lesson is embodied in a statement made in the movie Karate Kid Part II, in which Miyagi says to his karate student, Daniel LaRusso, "Never put passion before principle, even if you win--you lose," like the way I convey my frustration and anger to Harry for his having "dropped the ball" once I was in Nepal.

Several months prior to my leaving the United States, Harry had instructed me to make a list of all the equipment I would need for living in Katmandu and supplying my laboratory, as well as for working in the field. This I had done in detail. He said the equipment would be stored at the U.S. Embassy in Katmandu and would be awaiting my arrival.

There was, however, no equipment in Katmandu when I arrived, not even a blanket to ward off the cold of October nights. I had to borrow everything I needed to survive from personnel of the U.S. Aid Mission--people I didn't even know, which made me feel like an irresponsible beggar.

The more I thought about it, the angrier I got, but I didn't occur to me to find out why the equipment wasn't here. I just knew it wasn't and that it was not "my fault." So I wrote a letter to Harry--with a carbon copy to the commanding officer of the Naval Medical Research Unit 3 in Cairo, Egypt, which began,"Subject: INCOMPETENCE! When are you Sons-of-Bitches going to send the gear you promised me nine months ago would be awaiting my arrival at the U.S. Embassy in Katmandu?"I showed the letter to Walter Treadwell, a man who had been kind enough to help me ever since I had arrived in Nepal. Walt said, "Chris, this is a 'mad-letter,' and I wouldn't send it. Put it in a drawer over night and read it again in the morning when you've cooled off. There's a better way of saying it. The way you've said it now, while you may be right, will not give you the results you want. Besides, the letter doesn't have to be sent in such an all-fired rush. If you send it a week from now, that'll be soon enough."

I was twenty-seven, a very young twenty-seven, however, and, although I listen to Walt's words, I didn't "hear" them. He was right, of course, and his counsel was the wisdom of his experience. But I hadn't given the letter to Walt to garner his counsel; I'd given it to him to justify my position by winning his agreement with my point of view. When that was not forthcoming, I simply tuned out what he said. I was not in a space to be benevolent, because I was too busy being a victim filled with righteous indignation, and by geebers I was going to get the maximum mileage out of the situation.

Therein lay the mistake; I put the passion of my impatience, my lack of understanding, and my unequivocal condemnation before the principle of compassion, which demands patience, understanding, and mercy. I want what I want, and I want it now! I neither thought about possible extenuating circumstances on Harry's part--nor care. I had no mercy in my condemnation of what I deem to be inexcusable incompetence. After all, I was "right." The expectation I'd been given hadn't been met, and there was going to be hell to pay. So I send the letter the day I wrote it.

Well, I got all of the equipment within a month, but at a terribly high price. I neither saw nor heard from Harry again--until I spoke to him for the last time on his death bed. I'd embraced the world's curriculum of fear, impatience, and condemnation, and in so doing, I'd lost sight of love and compassion. I'd forfeited my friendship with Harry for a shipment of material objects.

Had I followed Walt's counsel of setting aside my passion in favor of compassion, of doing unto Harry as I would have had Harry do unto me, I could have had both--my friendship with Harry for another twenty or so years and the equipment, which I used for but a single year. But then, I didn't listen to Walt.

A few years ago, I was talking on the phone with my colleague, Bob Lewis. During our conversation, he told me that Harry, our mutual friend, was in Walter Reed Army Hospital with terminal cancer and a prognosis of less than two weeks to live. My inner voice prompted me to call him immediately.

I did.

The phone rang. Click. "Hello," said Harry quietly from his bed.

"Hello Harry," I answer, "you probably don't remember me, I'm Chris Maser."

He answered in his usual soft, but now feeble voice. "I remember you, Chris. I've been following your career all these years. I'm sorry I was so rough on you years ago."

"Harry," I reply, "we both know more now, and had we to do it over, knowing what we now know, we'd both do it differently. Besides, do you remember what you told me twenty years ago?"

"No," he replied.

"You told me that any study worth doing was worth publishing and that no study was finished until it was published and available to other scientists."

"I said that?"

"Yes, Harry, and with that you gave me a priceless gift, a gift that's guided me all these years, a gift I've passed on to others. All I can say, Harry, is 'Thank you.'"

Silence.

"Thank you for saying that, Chris. This is the most important phone call I've ever had."

In this long overdue interaction, I'd been graced with the opportunity to clean up my truncated relationship with Harry and to say "Thank you," "I love you," and "farewell" in a way that lightened his burden and mine. And Harry also had been given the opportunity to complete some old, unfinished business that he'd carried with him for so very long.

He died a few days later at his home in Cairo, Egypt, and I had yet another lesson in the importance of being present and acting in the here and now, because at any given moment I might not have another chance to say "I love you."

There's only one thing in life that we can and must conquer, and that's the unbridled, worldly passions within ourselves. In so doing, we lay aside the storms of our lives and we put to right both our homes and the world. This is but saying that the extent to which we align our lives with the Universal Principles of love and compassion, we live aright in harmony--and to the extent that we do otherwise, we suffer the consequences in like measure. This is the God-given choice of every human being. And when we choose God's curriculum, we have a miracle in your pocket every moment of our life.

In memory of Harry Hoogstraal. Harry (left) and Robert E. Lewis (right). Harry was the world's authority on ticks, and Bob is the world's authority on fleas. I worked with both of them while I was in Nepal in the mid-1960s.

In memory of Walter Treadwell who I got to know as a friend while in Nepal.

© chris maser 2008. All rights reserved.