Also see: My History in Forestry | Forest Trusteeship | Recommendations

"Chris Maser is rapidly becoming known throughout the Northwest as 'the Gandhi of the forest'—a man who is highly esteemed by conservation groups, but who is also respected by the Forest Service and even by some people in the timber industry because of his research in forest ecology and because of his conciliatory, nonadversarial approach to forest management issues."

Thomas I. Ellis

What's Happening 1988

"I had not thought about a lot of things, but Chris Maser here taught me quite a bit about what happens when a tree dies. I guess I just picked up one of his books, I'm not sure. But he was talking about what happens and how, with some of the older, bigger trees, it may take 900 years before the tree has gone through all its phases and is back once again as soil that it came from, nourishing as it had been nourished."

David Brower

Founder and Chairman of Earth Island Institute

"Last Wednesday, a group of 53 people, mainly members of resource agencies, industry, and Wall Street, toured Ft. Lewis in Western Washington to celebrate and showcase this Army Installation's Forest Stewardship Council certification.

"I will never forget a moment we had standing in dappled sunlight below the towering trees of Ft. Lewis's stunning forest. The whole group was hanging on Chris Maser's every word as he gave an explanation I'd never heard of the contributing phenomena of age in an old-growth forest in contrast to old-growth-like structure, humanly created. I scanned the faces filled with awe and felt huge gratitude for Chris, not only for just being there but also for being able to illuminate the wonders so few people get to know about."

Jean Shaeffer

Forest Stewards Guild

"The more we begin to understand how forests function as ecological systems, the clearer it becomes that modern forestry is akin to mining, not resource management, and precludes any hope of sustainability. In the forefront of scientists doing the fieldwork to back up these kinds of assertions is Chris Maser. He writes books in a style equivalent to an ecological food web—a careful look at process via a tangential combination of hard science, history and humanistic psychology.

"The Redesigned Forest contrast the ecological needs of a forest with current short-rotation forestry practices. If you want to understand his basic argument, start here. Forest Primeval is a biography of an ancient forest in Oregon, from its beginnings in the year 988 up to the present. From the Forest to the Sea is an example of the fieldwork Maser was doing at the Bureau of Land Management before he left to become a private consultant. It examines what happens to the biomass of fallen trees, in the forest, in the watershed, and even on the seabed miles off the Oregon coastline."

Richard Nilsen

Whole Earth Review. Spring, 1990.

"Another important forest value that Merv [Wilkinson] manages for it coarse woody debris, although, by his own admission, he hasn't always done so. About 15 years ago, Chris Maser, author of, The Redesigned Forest, visited Wildwood and told Merv he had a good operation, but it was a little too tidy. "I listened to that advice, and I can see the difference already," says Merv. "Now I leave from 8 to 10% of a cut on the ground. The larger pieces form habitat and nurse logs, and the smaller debris rots to form organic material for the soil. There is no need to use artificial fertilizers when nature can do it better and more efficiently."

British Columbia Silvicultural Systems Program

Notes from the Field. Vol. 3. July 1996.

"Another thing I have learned is how complex these things called forests can be. They are not just trees; they are complex ecosystems that include the dead tree where that flying squirrel is denning. Chris Maser, one of the most highly respected restoration ecologists in the world, has written eloquently on this subject. He speaks of the northern flying squirrel, which primarily feeds on fungi. Some of these fungi are mycorrhizal, meaning that part of the fungus actually grows around the fine root tips of trees. This is a two-way partnership. More nutrients are moved from water and soil to the tree because the root surface is increased and the mycorrhizae themselves are more efficient at this transference. In return, the trees provide sugars from photosynthesis to the fungi. These two-way relationships are not at all unique. What we are just beginning to understand is that there are three-way and four-way and who-knows-how many-ways relationships that are critical to forest ecosystems. Back to the flying squirrel. It eats the fungus, and spreads spores throughout the forest in its droppings. As if that weren't enough, the fecal pellets contain not only the spores, but also nitrogen-fixing bacteria and yeasts—they in effect inoculate the forest with spores and the nutrients they need to get growing."

Gary Schneider

Presentation to the Prince Edward Island Department of Agriculture and Forestry.

Fall 2003.

"I interviewed Chris Maser for an article about old growth and fire once. He is a very compassionate and highly regarded forest ecologist…"

James Johnson

Eugene, OR

FORESTRY WORKSHOP

There are six primary themes woven throughout my workshops on sustainable

forestry:

First, I recognize, as we strive to maintain sustainable forests, that we

are faced with the constant struggle of accepting open-ended change and its

accompanying uncertainties, which often gives rise to fear of the future

and a disaster mentality. We must therefore be gentle with one another and

do whatever we do with love because there are no "enemies out there," only

frightened people.

Second, ideas change the world; people change ideas. And people must change—raise the level of their consciousness—before ideas will change.

Third, the level of consciousness that created a problem in the first place

is not the level of consciousness that can fix it. To fix a problem, one

must elevate one's level of consciousness concerning the problem and its

solution.

Fourth, the way to avoid top-down regulations is to do such an excellent

job of land trusteeship the regulations are a moot issue.

Fifth, all we have of real value in the world as human beings is one another.

If we lose sight of one another, we will find that we have nothing of value

after all.

And sixth, the twenty-first century can be a time of people getting together

to heal the world's forests.

CONDUCT OF THE WORKSHOP

Although I have conducted forestry workshops in a number of ways and can

specifically tailor a workshop to fit the needs of a client, the two that

follow are the two most common, successful ways: (1) I require people to

commit four days to the workshop process in order to meld the abstract notions

of science and social values with the concrete practice of forestry in the

field and (2) I either require or am requested to add a fifth day because

there is some known conflict in peoples' differing views that needs to be

resolved as an integral part of the workshop.

The first day is spent learning how North American temperate coniferous forest

ecosystems function—both aboveground and belowground—based on the best

scientific data. This is coupled with a look at some of the problems that

have arisen over the years in Germany, Slovakia, and Japan as examples. By

viewing and discussing the problems that others have created and are having

to cope with, we can approach our own problems without feeling defensive.

The second day is spent in the field looking at and discussing the concepts

of the first day in order to render abstract notions into concrete experiences.

This field day is critical because most people think in concrete terms of

everyday experience and that is not only how they remember what they learn

but also fits an old Chinese proverb: I hear and I forget. I see and I remember.

I do and I understand.

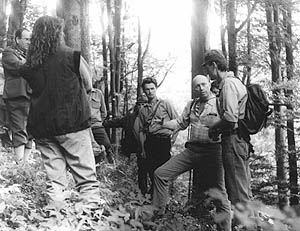

Conducting a field workshop for the Federal Forest Service, eastern

Slovakia.

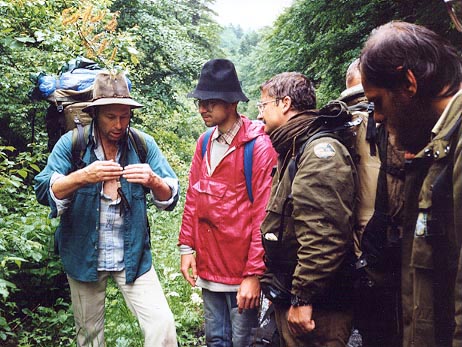

On a field trip with VLK (Wolf) Forest Protection Group, eastern Slovakia.

The third day is again spent viewing slides, but this time the ecology of

wood in streams, rivers, estuaries, and oceans in order to understand that

everything has ecological value and that the notion of "waste" is a purely

economic concept with no connection to the health of the forest ecosystem.

Put a little differently, people need to learn that efficiency and effectiveness

are not the same. When effectiveness is sacrificed on the alter of cost

efficiency, ecosystems lose their resilience and we set them up to collapse

inward on themselves.

Coupled with this data is a slide presentation and discussion of not only

how society uses ecosystems but also how society changes them and thereby

creates the circumstances of its future because one nation's forestry practices

on any given day affects the whole world for many generations.

The fourth day is again spent in the field discussing the notions and concepts

of the first three days in a way that the workshop as a whole becomes a concrete

and practical experience.

When a fifth day is added, it is always a day in the field at the site of

the conflict. The purpose of the fifth day is to seek a collective solution

to a particular problem in a particular place using the knowledge gained

during the previous four days.

UNDERLYING PHILOSOPHY OF THE WORKSHOP

With the passing of each decade our society becomes increasingly complex

and confused. We are mesmerized by numerical units (identification numbers)

and commodities, our attention riveted on manipulating the world for products,

such as timber, politically important wildlife, endangered species, ecotourism, and so on, while we lose sight of human dignity.

Tragically, it's this neglected area—human dignity—that is the barometer

of our well-being. The wholeness, the inner state of self-worthiness of each

member of society, is the individual mirror image of society's value system.

When that value system faithfully reflects the individual's fulfilled needs

for wholeness, then society and its components are in harmony. The paradox

is that managing products (board feet) is a numbers game, whereas human dignity,

which is based on spirituality, intuition, creativity, imagination, dreams,

and experiences, is not quantifiable.

In field and forest, in desert and ocean, Nature makes the choices. In human

society, the choices are ours. That we tend to avoid change, to hug our comfort

zone, does not diminish the positive option, it only means that we have chosen

to argue for our limitations instead of for our potential. To opt for one's

potential always involves an element of risk. And we, individually and

collectively, through our disaster mentality, tend to focus on and cling

to a view of impending doom because of the emotional discomfort in the

unpredictability of risk.

Although individualism is good, even necessary, in the embryonic stages of

an endeavor, it must blend into teamwork in times of environmental crisis.

Setting aside egos and accepting points of view as negotiable differences

while striving for the common good over the long term is necessary for teamwork.

Unyielding individualism represents a narrowness of thinking that prevents

cooperation, possibility thinking, and the resolution of issues. Teamwork

demands the utmost personal discipline of a true democracy, which is the

common denominator for lasting success in any social endeavor.

Even if we exercise personal discipline in dealing with current environmental

problems, most of us have become so far removed from the land sustaining

us, that we no longer appreciate it as the embodiment of continual processes.

Attention is focused instead on a chosen product—in forestry the production

of wood fiber—as a measure of the success or outcome of management efforts,

and anything diverted to a different product is considered a failure.

It is a critical time to re-evaluate our philosophical foundation of forestry,

society, and how we integrate the two. And it is time to re-emphasize human

dignity in our decisions. With a renewed focus on human dignity—present

and future—as a "product" of the resource decision-making process, we can

broaden the philosophical underpinnings of management into "caretaking," which includes the ecological sustainability of forests and grasslands, oceans and societies, rather than

only the exploitation of a few selected commodities they produce. Emphasis

on human dignity will help foster understanding and teamwork that in turn

nurtures mutual trust and respect rather that the "us against them" syndrome.

The "us against them" syndrome exists because our dreams are too small; they

are limited only to our own, personal interests and therefore appear separate and in

conflict. For example, I want old-growth trees, or I want wood fiber, or

I want wilderness, or I want to protect this endangered species (the spotted owl) or that endangered species (Fender's blue butterfly), or I want native trout, or I want

clean water, or I want ecotourism, or, or…. What we need instead is a collective dream large enough to encompass and transcend all our small, individual dreams in a seamless

way that gives them meaning, unity, and intergenerational sustainability.

If we dare to dream boldly enough, our special interests will both create

and nurture the whole—a healed, healthy, sustainable forest that includes

old-growth trees, and wood fiber, and wilderness, and spotted owls, and Fender's blue butterfly, and native trout, and clean water, and ecotourism, and, and….

Now, more than ever, we must recognize that we are part of the human family

and trust and respect one other as if human dignity truly were the philosophical

cornerstone of society. We must also recognize and accept that ultimately

we have one ecosystem—often called the biosphere—that simultaneously produces

a multitude of products. And we, as individuals and generations, as societies

and nations, are both inseparable products of and tenants of that system,

custodians and trustees for those who follow.

Today I see even more clearly that the past, the present, and the future

are all now, in this instant contained, and that the choices of what we do,

of where we go, is ours. And if perchance we make a mistake, we can always

choose to choose again. As long as there is choice, there is hope. As long

as there is hope, the human spirit will ever aspire to its highest achievement.

This said, there comes a point in the history and evolution of every individual,

profession, agency, and society when change is necessary if that individual,

profession, agency, or society is to continue to evolve toward a higher level

of consciousness. And it all begins or ends with the willingness of the

individuals—who collectively are the profession, the agency, and society—to

change.

A nation without the means of reforming itself is a nation without the means

of survival. The same can be said of a profession—any profession. Thus,

the profession of forestry cannot remain the same and survive; so those who

cannot or will not accept new ideas are destined to fall by the wayside.

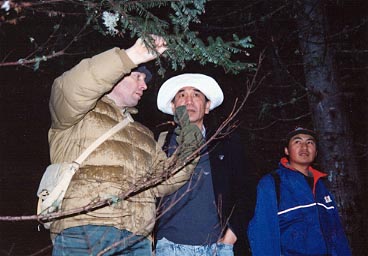

Siberians learning about temperate coniferous forests.

Physicist Albert Einstein faced a similar situation. He said that he felt

as though the ground had disappeared from under his feet when he was faced

with quantum physics and the uncertainty principle, because it meant that

the "modern perception" of reality was "wrong." All that he had been taught

to believe was "wrong." The whole basis of physics had to be rethought in

relation to a new set of principles, which, in itself, did not guarantee that

the new set of principles was correct, only different from those that proved

to be incorrect.

If it is difficult for students of basic physics to rethink their discipline,

it is even more so for foresters, because their concern goes beyond the

biophysical aspects of the forest to include social aspects as well. Thus

a forester's reality, which includes the relationship of people to Nature

and Nature to people, is now misperceived because both knowledge and social

values have changed. The forester's approach to forestry has become confused,

particularly concerning the social aspects of the discipline.

Society and science are today challenged to devise a new theoretical framework

based on a new set of metaphysical assumptions from which we can restructure

our social institutions—our world view. Pioneers in forestry glimpsed this

need of rethinking our social foundation during the reign of the conservation

ethic. They sensed that humanity's role in Nature was in error. But much

of this understanding was lost in the struggle to build a scientific basis

for forestry because the historical metaphysical assumptions about Nature

were inconsistent with the perception of Nature held by modern science. Our

Western industrialized society is therefore in a spiritual crisis because

we've lost our sense of place in and of Nature.

I say this because we must have a biologically sustainable forest before

we can have a physically sustainable yield of forest products—any forest

products: clean air, quality water, fertile soils, wood fiber, or endangered species (such as spotted owls and Fender's blue butterfly). I see few sustainable forests and little sustainable forestry as I look around the world because the majority of the timber industry is summarily cutting the forests down and, where possible, replacing them with fast-growing, economically motivated and designed tree farms. (A tree farm is a simplified and specialized area under cultivation as an economic crop of selected trees.)

Making a film about sustainable forestry for Japanese schools.

Although liquidation of the world's forests in favor of fast-growing tree

farms to maximize quick profits seems rational enough in the short term,

it may not be so rational in the long term. Throughout our habitation on

Earth we have developed our technologies on the assumption that the autonomous

biosphere, which produces the environment needed for life, is beyond our

ability to destroy. The day has arrived, however, when the life system itself

is within reach of our technology and our power to disarrange and destroy.

This is a danger no age has ever faced before.

In light of this danger, I propose a new paradigm for forestry, one based

on a special part of us, the part we seldom see when we look into society's

mirror. That view, so carefully hidden from ourselves, is our ability to

love, trust, respect, and nurture both one another and the land. To have

sustainable forests, for example, we must change our thinking; and to change

our thinking, we must transcend our own special interests and our own local,

regional, and national boundaries to encompass all interests in the forest

as a global society—present and future. Such change will cast a lighter,

cleaner image in society's mirror, one that integrates Nature's design of

a forest with society's cultural necessities in an attempt to achieve

biologically sustainable forests and sustainable forestry.

If the twenty-first century is to be the time of caretaking and healing the forests of the world, we must each be willing to raise the level of our consciousness and work together as people who care about our own future and that of our children, their children, and their childrens' children. To heal the forests, we must be willing to share openly and freely any and all knowledge necessary to achieve that end. In addition, we must be willing to cooperate with one another in a coordinated way, for cooperation without coordination is an empty cup. That means focusing on the healing of one another's forests while honoring one another's culture, even if we do not fully understand

it.

"Private forest owners, which make up about 40‰ of the forest lands in the N.W., have made some movements towards sustainability, not because it is the right environmental thing to do, but because people

like Jerry Franklin and Chris Maser have proven that it is the right economic thing to do. If forestry is to continue at all, new methods, which protect and enhance the soils, have to be, and are being, adopted"—Rob Sandelin.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, READ:

IF YOU THINK I CAN HELP YOUR GROUP, AGENCY, OR COMMUNITY, PLEASE CONTACT ME

TOP | HOME | SITE MAP | RÉSUMÉ | SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY | VISION AND LEADERSHIP

CONFLICT RESOLUTION | ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION | FORESTRY | PUBLIC SPEAKING | BOOKS

STORIES | MUSINGS | ESSAYS | CONVERSATIONS WITH FEAR | LIFE SERVING LIFE | BIBLIOGRAPHY

SELECTED SPEECHES | LINKS | SEARCH SITE

Chris Maser

www.chrismaser.com

Corvallis, OR 97330

Copyright © 2004-2011. All Rights Reserved.